The Industrial Revolution began in England in the 18th century, reaching its golden age in the 19th century. The energy generated by steam was soon joined by the almost infinite possibilities of electricity. However, few people know that compressed air was also a main competitor of electricity in terms of versatility for a long time in France. While other countries were experimenting with urban networks of electric clocks, Paris created a network of pneumatic clocks.

The concept of ‘master’ and ‘slave’

While tower clocks and bell towers were sufficient in ancient times, the increasingly frenetic world of the 19th century made it imperative to ensure consistent public time. To achieve this, the ‘master-slave’ concept was introduced, regardless of the signal transmission method.

A highly accurate, reliable and consistently precise clock, known as the ‘master’ clock, served as a reference source. Every minute, a signal was sent to all the secondary clocks, distributed throughout the territory, to advance them by one minute. These secondary units were called ‘slaves’.

The invention of pneumatic clocks

The patent for a network of public clocks synchronised using compressed air pulses dates back to 1877. It was signed by Popp, Resch and Mayrhofer and filed in Vienna. The first network of city clocks powered by compressed air was established in the Austrian capital. This successful experiment received widespread press coverage at the time.

France, of course, could not allow itself to be outdone, so one of the inventors, Viktor Popp, established the Compagnie des Horloges Pneumatiques in Paris. The newly formed company was entrusted with the exclusive task of creating the city’s network of pneumatic clocks.

Despite the fact that Resch and Mayrhofer were also co-owners of the patent, Popp had acted independently. Anticipating substantial profits, he acted preemptively, but this move soon proved to be ill-advised. Not only did Resch and Mayrhofer sue him, but Popp also proved to be an inept entrepreneur. The company soon changed hands and became the property of a group of banks.

An incredible structure

Why should we remember the pneumatic clocks of Paris? Certainly, it is due to two extraordinary characteristics: the extensive distribution network and the capillarity of its reach. While electric public clocks being tested in various cities were limited to a few dozen units along the main streets at most, Paris was different.

The network designed by Popp carried the signal not only to peripheral timepieces distributed throughout streets and squares, but much further afield. A vast network of pipes was necessary for conveying compressed air to the peripheral clocks, which were installed in large buildings, stations, industrial estates and even private homes.

The Central Station

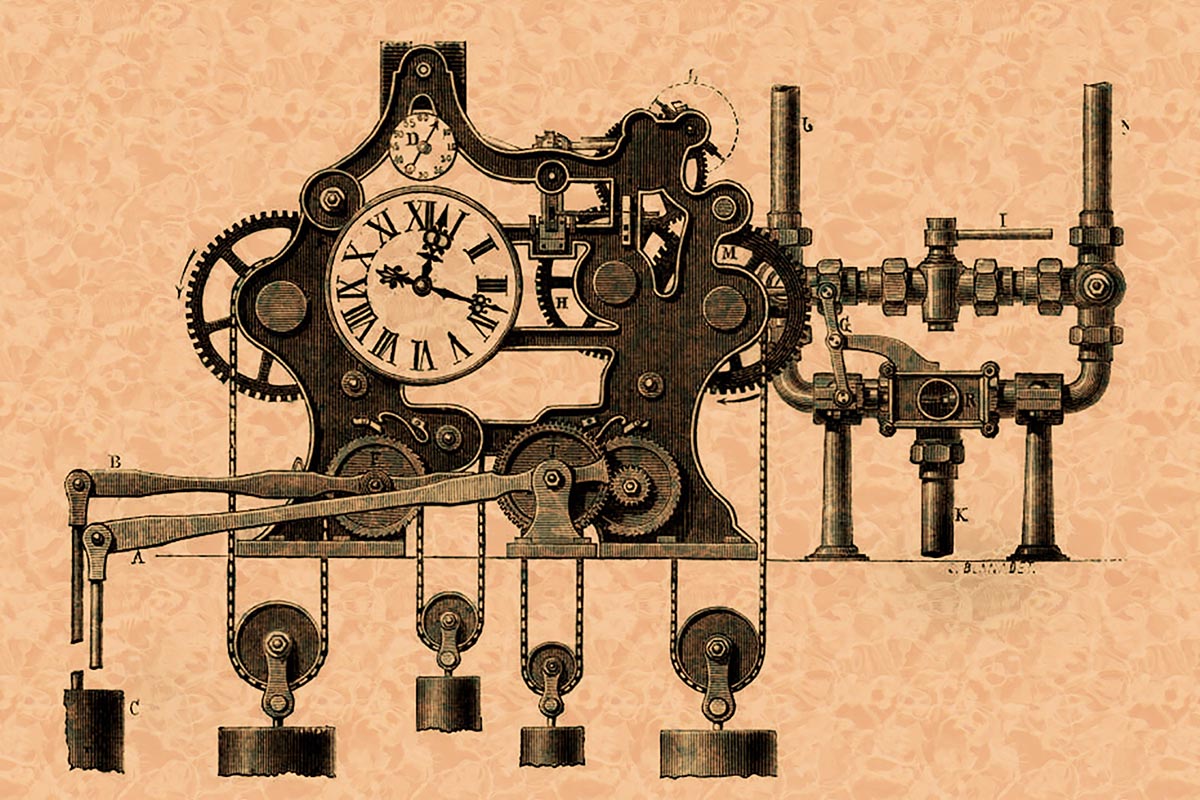

The system was complex, consisting of cascading compressed air tanks. To simplify this, the master clock released an impulse consisting of a burst of air at the end of each minute. This travelled through iron pipes to the satellite units, advancing them by one minute.

The master time was provided by a large central tower clock, which was synchronised manually with the signal from the Astronomical Observatory. Every day, an employee known as the ‘controller’ went to the Observatory in person at noon to record the exact time.

The master tower clock was modified to control the transmission of pressure signals through the network. In fact, there were two master clocks, with the entire system duplicated to ensure there would be no service interruptions in the event of a failure. As can be seen, the concept of redundancy was already well understood and in use in those days.

The shortcomings of the pneumatic clock system

Anyone with even a basic understanding of technology will realise that electricity and pneumatics are not equal. The transmission speed of the pressure pulse was much slower than could be achieved electrically. This was one of the most serious criticisms aimed at the system by its detractors. However, skilled salespeople responded to this objection by suggesting that customers requiring greater precision contact the Astronomical Observatory.

The propagation time was significant and could not be ignored.

Furthermore, the pressure drop caused by extending the network meant that it was impossible to manage the entire city from a single control centre. In fact, a series of sub-masters had to be used. Bear in mind that the pipes, most of which ran along the sewer network, extended for several hundred kilometres.

The slave clocks, i.e. the signal receivers, were simple units in which the movement of the minute hand was achieved by a pressure pulse transmitted from the pipe to a small internal ‘lung’.

Incredible numbers and incredible stories!

The success of the pneumatic clocks in Paris was remarkable. By 1890, it is estimated that there were more than 10,000 clocks in use in public, corporate and private spaces. A subscription was required for connection to the pneumatic time system, with the cost depending on the number of clocks installed. Clocks for domestic use were also supplied, complete with an alarm.

Even more frighteningly, I remember reading something terrible in the newspapers of the time. The Société des Horloges Pneumatiques offered private individuals the opportunity to convert traditional mechanical clocks into units equipped to receive the pressure signal at a low cost. Unfortunately, the original mechanics were discarded and replaced with three gears and a small air lung. I dare not think how many beautiful clocks were sacrificed on the altar of progress!

The decline of pneumatic clocks

Around 1910, however, the competition between compressed air and electricity came to an end. Electricity’s advantages in terms of power and signal transmission were clearly superior. By the end of the 1920s, the entire pneumatic time distribution network in Paris had been decommissioned, marking the end of an era. Occasionally, a few peripheral units can still be found on the second-hand market, serving as reminders of a bygone world and technology.